This morning's editorial, "Paying Price for Assault on Coal," joins the long list of previous war-on-coal opinion pieces. Unlike a number of these editorials, however, this one cites some statistics beyond the usual "$1000 electric bills" that is sometimes used to support the editorial's points. Unfortunately, the statistics are cherry-picked and may even be irrelevant to the conclusion.

The editorial tells us:

During the 2011-16 period, the average cost of electricity sold for residential use in the United States went from 10.4 cents per kilowatt hour to 12.75 cents. That is an increase of nearly 23 percent.

Some of us still enjoy low-cost power from coal. Here in West Virginia, where most electricity still comes from coal-fired generating stations, the average cost last November was 11.72 cents per KWH.

But in a preview of things to come if the government’s assault on affordable power continues, look at prices in California (17.97 cents) and Massachusetts (19.15 cents). Neither state has significant coal-fired generating capacity.

Given that conclusion you would expect then that the cost of electricity is directly related to "coal-fired capacity." However, a look at the source of the editorial's information, the U.S. Energy Information Agency, suggests that there is little correlation between capacity and what consumers pay for electricity. For example, which state in the EIA's nine state South Atlantic region pays the least for electricity? West Virginia, the region's biggest coal producer? Nope, we are the fifth lowest. Georgia is first and we're behind a state with very little coal capacity -- Florida. If you go to the source, look at EIA's Pacific region. The editorial singles out California (probably because we see them as a "green" state) where residents do pay significantly more than West Virginians. But the editorial ignore the two other western green states, Washington and Oregon, which came in at 9.51 cents and 10.75 cents compared to West Virginia's 11.72 cents. (An interesting side note -- last year Oregon banned all coal-fired power plants by 2035.)

Okay, the cost of electricity in a state has very little to do with its coal generating capacity. What is connected to the cost of electricity? I'm not an economist but I would probably first look at a state's power plant regulations and then the plants ability to pass on costs to the consumer to answer why some states pay more while others pay much less. For example, I googled "California and cost of electricity" and quickly found an LA Times analysis from last week that suggested as much:

California has a big — and growing — glut of power, an investigation by the Los Angeles Times has found. The state’s power plants are on track to be able to produce at least 21% more electricity than it needs by 2020, based on official estimates. And that doesn’t even count the soaring production of electricity by rooftop solar panels that has added to the surplus.

To cover the expense of new plants whose power isn’t needed — Colusa, for example, has operated far below capacity since opening — Californians are paying a higher premium to switch on lights or turn on electric stoves. In recent years, the gap between what Californians pay versus the rest of the country has nearly doubled to about 50%.

If you click on the link, you will not find any blame for the source of the electricity.

And then there is this much-cited recent study from the University of Texas at Austin's Energy Institute: "The Full Cost of Electricity":

Natural gas and wind are the lowest-cost technology options for new electricity generation across much of the U.S. when cost, public health impacts and environmental effects are considered, according to new research released today by The University of Texas at Austin.

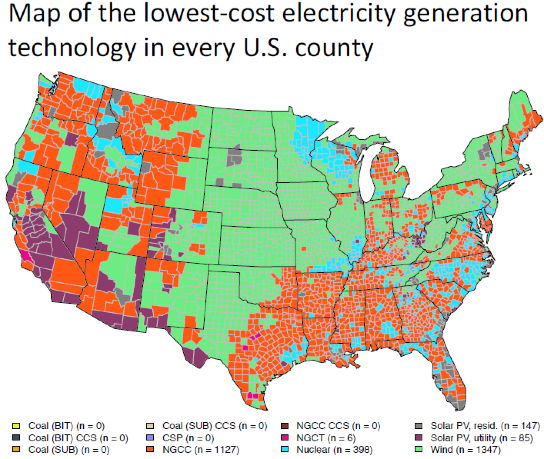

The study has a number of interactive maps of the United States that allow the reader to see the cheapest form of energy for every county in the United States. For example:

When all costs were considered, coal did not fare well. (Wind is the cheapest source in 1,347 counties including Ohio and neighboring counties.) As Power Magazine concluded:

Notably, coal-fired generation was not the cheapest option in any county when externalities were considered. Incoming president-elect Donald Trump has promised to revitalize the U.S. coal industry, though most experts suggest there is little he can do over the long term because of a range of macroeconomic trends that are working against coal-fired power.